Verifiable Electronic Voting

In short: power is corrupting. People who want to get in power and stay in power are not averse to cheating in elections. To make sure it is as hard as possible to cheat in an election we have lots of procedures around it; everything from how you are identified in the polling station via how you fill out your vote in the seclusion of a voting booth to how your vote mixes with all the other votes in the ballot box to make sure that no-one knows how you voted. We also have lots of observers making sure that nothing adverse is going on.

Still, it seems like something goes wrong in every single election. Someone makes a mistake or outright tries to cheat.

It is not good enough that elections are this messy. They are so fundamental to our democracies and thus the way we live our lives that they have to be correct. We need to zoom out, look at a bigger picture and try to figure out what elections should really be like. My suggestion: elections should be verifiable. Every single voter should be able to check that her vote has been properly counted (and not dropped behind a cupboard, forgotten in a warehouse, delivered to the wrong post office or spoilt by election workers) and everyone should be able to check that the vote has been done correctly.

The problem is: how do you make an election completely verifiable while keeping the votes absolutely secret? Without vote secrecy, the election is not open and fair and so need no verifiability.

In the last few years the Verifiable Electronic Voting research community has suggested a number of different ways of doing this and I would like to explain how the Prêt à Voter system, invented by Professor Peter Y. A. Ryan and currently developed by a research group at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK, works.

The Prêt à Voter system is based on a ballot form which has a candidate list with a random order from one form to the next. This means that if you look at two forms side by side, they will have the candidate lists in different order and this in turn means that if you mark your choice on one of them and then remove the candidate list, I won’t be able to tell from the bit remaining what your vote is for. Here are two ballot forms, compare the order of the candidate lists:

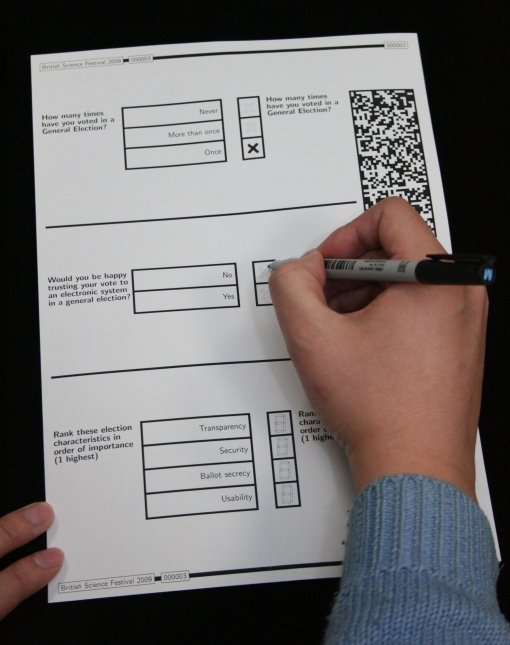

So in order to vote you are given a random ballot form by a poll station worker. It is probably placed in an envelope so that no-one can see the order of the candidates. When you are alone in the voting booth you take out the ballot form and make your selections:

When you are finished making your marks on the ballot form, you tear along a perforation, splitting the ballot form in two: one part containing the candidate list and the other containing your marks and a 2D barcode:

Your next step is to destroy the candidate list. You do this whilst still in the voting booth so that no-one has a chance of getting a glimpse of your candidate list. This means that when the candidate list is destroyed, you are the only person who knows what your marks on the remaining bit of paper means. Destroy your candidate list by shredding it:

You can now safely come out of the voting booth. From this moment your vote is encrypted and you are the only one who knows what it means. You can show it to anyone and you can have it scanned by poll station workers:

Because the vote is encrypted it can be scanned, submitted, stored (and eventually counted) centrally and published on a website for anyone to see – including you. So you keep your encrypted vote as a receipt. When you get home after voting you can check that your vote is among the votes counted by comparing your encrypted receipt to the one on the website. Here is an example of an encrypted vote and the digitally signed receipt that you get to take home:

Note that what you verify on the website (note that information might also be published in the newspaper, shown on TV and distributed in many other ways) is that the marks you made are the same in the electronic, counted, version of your encrypted vote. The verification step does not show how you voted as it does not display the candidate list, only the list of marks on your encrypted vote.

After the close of the election the votes are decrypted in such a way as to hide all the voters’ identities and (after many cryptographic steps, spread out on many different parties) verifiably producing the plaintext, countable votes. This procedure is very complicated and require computers to do all the cryptography but this can be done by experts. Because of the way that the system is constructed, it is not possible for any single person or any single organisation to change the outcome of the election or to find out how you voted. Instead, we spread out the trust in the system on many different parties who are unlikely all to work together to break the election, for example the current government, the opposition, each political party, the United Nations, several governments of other countries etc. Unless all of these come together and decide to change the outcome of the election then no-one can do so. Unless they all come together and decide to find out how you, or any other voter, voted then no-one can do so. This is a much better way of trusting elections than having to trust that an enormous apparatus, involving thousands of people, millions of voters and millions of votes works without a problem.

Photos taken by Dr Chris Culnane at the University of Surrey, UK – much obliged!

Pingback: Could This Electronic Voting System Make Fraud Impossible? | Gizmodo Australia

It seems problematic to the goal of secrecy to encourage voters to identify their ballots on a website from their home computers. While other aspects of the vote counting are distributed in this plan, the verification process seems to be a potential single point of failure that is impossible to protect from a corrupt body or outside interests, and is unnecessary to the execution of a fair election. The rest of the plan is indeed elegant, so I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this point.

The system is built in such a way that if a portion of all the voters check that their votes are correct then this gives a level off assurance that all the votes in the election have been recorded and counted correctly. It is therefore not essential that every single voter checks her receipt – a certain number of voters won’t care enough to do so, others won’t want to. However, it is by no means unnecessary that voters do check that their votes have been recorded and counted correctly – the purpose of these Verifiable Electronic Voting schemes is specifically to make the elections verifiable in this way. Voters check that their votes are fed correctly into the system and then anyone can check that the votes are correctly decrypted and counted.

Kenneth, if on the other hand you meant that the checking of the vote at home after the election would let people eavesdrop on Internet traffic and find out how you voted then the answer is simple: the votes are encrypted and the checking of your encrypted vote against the encrypted vote on the website does not reveal how you voted. The secrecy requirement is even higher: you are unable to use the receipt to prove to anyone how you have voted and this is to ensure that you cannot be forced to vote in a specific way or sell your vote. The receipt you get is simply an encrypted representation of your vote and you are the only person who knows what this means so you can show it to anyone.

Surely the vote needs to be decrypted with the information in the barcode as to which vote is which so that they can be counted. Surely then the key to do this would need to be public (if news media was to be able to count it themselves), and therefore one can now link a particular vote to person as one only needs a copy of the very public key to decode the vote to figure out who voted for what?

Unless you are willing to release more information on the cryptography being used?

No, the key that is used to decrypt the votes is secret and it is split into a number of key shares that are in turn held by a number of different trusted parties (such as all the political parties, the government, the UN and other organisations) such that it is unlikely that they all work together to break the secrecy of the election and find out how a holder of an encrypted receipt has voted. The public verifiability, that is to say the checking of the decryption of the votes (performed by the trusted parties who have key shares) and the counting of plain-text votes, is not dependent on knowing the secret key – but perhaps the corresponding non-secret public key, which is published.

Thanks for the clarification. I misunderstood what data is to be presented to the voter for verification. The most that could be discerned is that a particular voter cast a ballot, not what votes were cast. I’m on board!

I’m an Officer of Election in the US and have been running the voting machines at my precinct for the last few years. I’d love to be able to give voters assurance that their votes are being counted.

Pingback: Gizmodo of the Day « from the moon and beyond

Hi.

The one thing I don’t get is where exactly the difference to a plain old “make your cross and put the ballot in the sealed box” voting procedure is.

At the end of the whole business a scanner seems to be detecting crosses drawn on paper and counting these. So why adding this extra barcode and “have your ballot back” layer at all? If you have memory problems, just take a photo of your vote.

The receipt that you get to take home lets you check that your vote has actually been counted. As you have correctly noted, it is not that different voting in Prêt à Voter to voting in a normal paper-based system – the difference is the verifiability. Each voter can check that her vote has been counted, as opposed to old systems where you have to trust lots of procedures to trust the outcome of the election.

In Colombia, where I live, the main way elections are rigged is by paying (with money, merchandise or jobs) citizens to vote for a particular candidate. The person or party doing the paying can’t know for certain if the voter voted for the designated candidate, but results for each voting station are made public and this data can be cross-checked with the data on which voting station is assigned to each citizen (this is also public) to have an approximate certainty. Out of 100 citizens assigned to vote at a specific voting station, for instance, a candidate may have paid 30 people to vote in his favor. He’ll know if he got his money’s worth if at he obtains at least those 30 votes; that’s as close as he can come to knowing if he wasn’t cheated back.

It seems that the system proposed here would not only not eliminate that kind of election-rigging, but would actually perfect it, since the corrupt candidate could know for certain if the voter who took the money truly voted for him/her or not.

I am sorry, but you have misunderstood the way the system works. The system does NOT, I repeat NOT, reveal to anyone how any particular voter has voted. Instead the system is constructed in such a way as to allow the voter, and no-one else, to verify that that her vote has been recorded and counted the way she cast it without ever jeopardising vote secrecy.

Precisely. The corrupt candidate could demand the voter turn over her part of the ballot to make sure she voted for him, or she wouldn’t get paid.

The voter’s part (you mean the encrypted vote, or receipt) does not show how the voter has voted so the answer is no, a corrupt candidate cannot do this. The voter cannot prove how she voted using her receipt and so cannot sell her vote in this way. The voter can use the receipt to check that her vote has been recorded and counted correctly by comparing the marks on her receipt with the marks on a website (or in the newspaper for example). But remember, the receipt contains only the marks – not the candidates!

So there is a technology, which can decrypt the encrypted vote in order to count them. How does it work and why is it impossible for anyone else to decrypt the encrypted vote? What is the information on the Barcode and why is noone else able to youse my ballot + barcode to encrypt. (Everyone is able to verify the votes.)

The decryption of the votes can only be done using a key which has been split up in a number of keys and given to various different people for safe keeping. So each of the political parties may have a key share, the government another, the UN their own part and so forth until you feel that enough different groups are managing a key share. The secrecy of the system is based on the unlikely event that all of these people work together to break the election. That is much better than having to trust a single election authority to keep your vote secret and safe.

To pursue this line of thinking: Someone in the above comments mentioned that one could take a photograph of a ballot while in the voting booth. Potentially, a person who is selling her vote could secretly photograph the ballot to show as evidence of how she voted, and then shred the actual ballot. Then she would walk out of the voting booth with the receipt portion, plus a concealed photograph of the ballot portion.

It would seem infinitely difficult to guard against people concealing photographic devices of some sort when they go into the polling booths. Unless you have an answer to how this way of cheating can be circumvented, Thierry Ways might indeed be correct that the system cannot eliminate widespread election rigging.

One thing is clear: camera phones are very helpful when it comes to vote buying or coercion, regardless of what voting system is in use. In the traditional paper ballot setting, I can make a small video of myself filling out the ballot form in the voting booth and this would satisfy a coercer that I have complied with his demands. To cheat the coercer is difficult (I have to make the video, spoil the ballot form and procure a new one) and I may be afraid to try to do so anyway. Using voting machines, essentially computers that you interact with to cast your vote, you can easily just make a video of the whole process leading up to the machine indicating that your vote has been recorded. My coercer could even set it up so that I send him the video of my vote using MMS or email as soon as I come out of the polling station and the money hits my bank account the following day.

I really do think that camera phones are a threat to free and fair elections. The only way I can see that we can deal with this threat is to make sure people are not using camera phones or other recording equipment when they are voting. If this means making people lock up their electronics on the way in to vote or setting up the voting booths in such a way that people cannot see your vote but they can see if you try to record what you are doing, I don’t know. This is not my field of expertise and this is something that has to be handled by election officials around the world regardless of what voting system (paper or electronic) they are using.

In some e-voting schemes, voter is allowed to vote multiple times, so that one can vote another time later (remotely) to invalidate the coercer’s choice.

That is indeed so, and if election officials in a country decide that this is a good way to combat the threat of recording devices in poll stations then it would be possible to set up Prêt à Voter in such a way that a voter may vote however many times she wants but only the last vote she cast counts.

Ok, but does pret a voter supports multiple voting and discarding the previous votes? i.e. what happens if coercer tries to validate the invalidated vote?

We work with Prêt à Voter in the polling station setting where your privacy is safeguarded in the traditional way, by ensuring you are alone in the voting booth when you prepare your vote, so we haven’t really worked very much on a multivoting option. When I think about it though, it does seem possible to set the system up such that you can verify each cast vote but only the last counts and it is verifiable that only one vote per voter has been counted, and that the correct vote has been counted for each voter. This last bit requires a lot more thought though.

I think there is a lot that goes on in the encryption of the vote. What is posted on the web to give the voter confidence that the vote, he/she made is counted “correctly”?

The voter goes onto the website to check that the marks she made on her ballot form before it was scanned are in the same positions on the website. This indicates that her vote has not been changed, and, combined with the publicly verifiable decryption of the votes and the audit of ballot forms, this gives her confidence that her vote has been counted correctly, i.e. that her vote has been counted as a vote for the candidate that she wanted to vote for. There is a lot of cryptography going on in the system and the average voter should not be expected to understand or be able to verify that it happens correctly. Instead the system, and the numerous different parties taking part in for example the decryption of the votes, publish election data that is free for anyone to download and check using their own methods and software. This would reasonably mean that the different political parties, a number of media companies (newspapers for example) and other interested groups and individuals will check the parts of the system that the individual voter cannot. This is called public verifiability.

So in summary, the only thing most people will check on the website is that the electronic version of their encrypted votes match the receipt they have in their hands.

David, how does a voter pick out which scanned image, from a database of at least thousands, should be compared to his/her receipt? The photograph above of a receipt and a scanned image do not appear to have matching barcodes, even though they look like they might have a matching alphanumeric code (it’s hard to read). So while it is statistically very likely that there are other receipts that look the same as mine in terms of which boxes are checked, the thing that must be compared to be sure that it is MY receipt image is not totally clear to me.

Also, could you explain in a little detail how the reliance on cryptography and the reliance on widely dispersed counting can be balanced? An open secret is no secret at all. If a corrupt agent (politician, gang, corporation, etc.) had access to the software used by the many counters, then couldn’t they know how a person voted?

1. Each encrypted vote has a serial number which allows you to easily look up your encrypted vote online so that you can check that it has been recorded and counted correctly (again, this does not leak how you voted but allows you to quickly look up the encrypted vote).

2. There is a cryptographic tool called threshold cryptography. This simply means that the key needed to decrypt something is split into several keys and you need a certain number of these keys to perform the decryption. So what you can do is split the key that can decrypt the votes into a number of parts and then give these parts to different people to keep secret. Unless a threshold number of those people loose, leak or give away their key parts, then the encrypted votes are safe. So unless a number of trusted parties work together, no-one can find out how a person voted.

Congratulations. Excuse me. What if a voter does NOT destroy the candidate list (whilst still in the voting booth), but instead simply hides it in his pocket and brings it home? Why can’t a corrupt candidate buy votes, asking the voter to send him a picture of both the receipt AND the candidate list, as a (not perfect) “proof”? Wouldn’t it be better if the list was destroyed under the eyes of both the voter and poll station workers, OUT of the voting booth? (Of course after having folded the list, so that poll station workers can’t get a glimpse of it). Maybe, or for sure, my solution isn’t good, but is my question good? Thanks.

You have identified a problem that has been recognised for some time: if the secrecy of the election is based on the destruction (shredding) of a piece of paper, how do we make sure that people actually do destroy that piece of paper – without them having to show the piece of paper to anyone? There are a number of possible solutions to this problem, such as the voter being required to put the candidate list (left hand part of the ballot form) into an envelope which has a window through which you can read the serial number of the ballot form and then forcing the destruction of this envelope under the inspection of poll station workers.

One can do many pictures in the privacy booth as one likes — there is no authenticity proof as the pictures can be altered.

Perhaps the part with candidate list should not be identifiable, i.e. it should not contain any ID.

Once this list is detached, it is no different than any other print, i.e. anyone can print such a list.

Well, except perhaps the unique tearing of both papers could help linking them in authentic way, but then the ballot form could be designed in such a way that the officer would detach and destroy the narrow middle strip between the candidate list and the vote (upon scanning) — this way there would be no matching and the voter could keep the candidate list and the vote.

Great idea about always removing a middle part of the ballot form so as to remove the fibres in the paper close to the perforation between the two ballot form halves. It has been shown that it is possible, using only a standard magnifying glass, to match the fibres of two pieces of paper that have been cut apart.

My problem with having a camera phone in the voting booth is that eventhough it is possible for a voter to fake voting in a specific way and handing over the film he shot with his camera phone to a coercer, this is pretty tough to do. And if lots of people are asked to film themselves filling out the ballot form then quite a few of them would not be confident in faking it and would thus be coerced.

Even better yet, one can put a bin into the voting booth with a note:

honest citizens put the detached candidate lists here,

others can take any of them with them selves (and sell, or whatever).

Initially, the bins can be pre-filled with lists from auditing.

This bin would facilitate a cheap tool of providing abundance of meaningless candidate lists in countries where printing is not so accessible, and thus publicly discouraging buying the candidate lists as a kind of proof of some vote.

Similar technique is used in off-the-record communication encryption, where the developers also provide tools to forge any possible conversation (for deniability purposes) in case a third party wants to use encrypted data as a proof of signed information.

PS

I asked that question because in some countries it is illegal to take smartphones and cameras in the voting booth.

I definitely agree that camera phones (both still pictures and video) are a threat to the secrecy of an election. I think it is a possible way of having voters prove to you that they have done as you asked and as such, I don’t see any other solution than making sure that people are not able to bring their smartphones into the voting booth or making sure that they can’t use their smartphones without people (poll station workers) seeing that they do so.

So, I can check that my vote for party ABC was counted. Good. And maybe I can see another 199 votes for ABC and another 400 votes for DEF, which tells me that DEF has won the election (or, at least, will have a 2/3 majority in parliament). But who tells me that the 599 votes that I see are counted correctly?

In other words, the average citizen is not even expected to understand how the system works, much less to be able to verify that votes were counted correctly.

Indeed, the cryptography is so complicated that we can only expect experts to understand it fully. Therefore some parts of the system are not verifiable by the individual voter but by the electorate as a whole (we call this public verifiability). In other words, checking that the votes are decrypted and counted correctly can be done by a large number of different experts (mathematicians, cryptographers, IT consultants etc) working for the people (in the form of media, newspapers, political parties of all flavours, international observers and the like) so that we can be very sure that the work has been done correctly. All the data that is needed to do these checks is published online so that anyone who feels so inclined can download it and check it using software that they themselves have programmed.

How can the media help verify (for reasons of public verifiability as you mention) that the counting is correct, without having all the keys from the different parties? If they do have access to these, it sounds like there are several people able to decrypt the candidate list for any given ballot.

Another thing, the system seems to rely on some “superadmin” which will assemble the key from the independent parties subkeys, input this into a computer which will decrypt the ballots and do the counting. This will then be the only person able to tell if the voting is correct. Why would he be incorruptible? If there are several “superadmins” to whom the final decryption key will be known, the result will have more “public verifiability” but also be more prone to corruption in terms of verifying bought votes?

1. There is a private-public key pair such that something encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the secret private key. The verification of the decryption is only dependent on knowing the public key, not the private key and therefore the secret key remains secret.

2. In the cryptography literature there exist schemes whereby a shared secret key can be created without any one party knowing the “whole” key. As you have correctly identified, there are also such schemes that use a central point to create the key shares and give them to the various parties, but this would then, for a while at least, place a burden on this central point not to leak the key. So no, there is no superadmin and the system is specifically set up with lots of different trusted parties, all of whom have to work together to break the election, so that there is no one person who has to remain incorruptible.

Dear David,

Nice work,, especially for the attention to larger social issues.

But, indeed, I think this thread very precisely locates the major problem. You say:

“There is a lot of cryptography going on in the system and the average voter should not be expected to understand or be able to verify that it happens correctly.”

Thus, I vote, and then I go there and check that my voted is counted – fine. But I cannot possibly check that my vote has been counted correctly.

This is the dilemma, if you prefer:

-The old system asked me to me trust my party representatives who verify the counting as it goes on.

-The new system asks me to trust encryption plus experts plus, once more, my party representatives who understand encryption and expert talk!

I think the dilemma is a simple one, ins’t it.

Moral: The tradeoff between secrecy and transparency is not easy, and before moving out of the present equilibrium point (the standard voting system) a lot of further work is required!

Most cordially

Roberto

Yes, someone who wants to check that all the votes are correctly decrypted and counted will have to read up on the theory behind the system and the different technical specifications – and really, become an ‘expert’. But the positive thing is that we can have a very large number of experts, so that if you don’t trust my expert, you can find your own. Each political party may well commission several experts of their own to verify the election and if you don’t trust the experts of party A, then you may feel more comfortable trusting the experts of party B. If you don’t trust either of them, then newspapers and other media outlets as well as international organisations (let’s say the UN for example) also appoint experts to do the same verification. If you still do not trust any of these you can potentially read up on the theory and technical specs and write your own piece of software that does the verification for you.

This is quite different from the kind of “code verification” that happens in some places around the world, where the code is considered a trade secret and only a handful of experts, or even just a single expert, is allowed to look at it.

It seems to me that there is a component missing from your system. You have a way for independent groups to verify that the final count corresponds to the posted votes, and you have a way for an individual voter to verify that his or her single vote was posted correctly. But how can an independent group verify the accuracy of the posted votes overall? A voter can check a vote anonymously, but can they challenge the vote or complain anonymously? If there are sporadic reports of missing or altered votes, does this indicate a few isolated errors, or a rigged election? Suppression of complaints leading to an under reporting of fraud, or a disinformation campaign (by disgruntled losers) leading to over reporting both seem possible.

So voter verifiability plus public verifiability makes end-to-end verifiability. The way the electorate (the public) verifies that the votes have been cast by eligible voters may for example that a list of voters who have voted is published. That the encrypted votes are recorded, submitted and stored correctly is checked by the individual voters. Then all of this data is decrypted by a large number of trusted parties (such that they won’t all work together to break the election, see other comments) and finally are the plaintext votes counted. The decryption and counting of the votes is verified by the public (probably in the form of a large number of different experts hired by newspapers, political parties and others to do the actual, mathematical checks).

The purpose of the encrypted receipt is also to give the voter possibility to challenge the election if her vote has been altered. Whether or not isolated cases of changed/dropped votes are a sign of major fraud or isolated errors is really up to a court to decide after all proof has been collected and published in the open. A major hurdle to adoption of these complex but verifiable systems is disinformation campaigns, as you point out. Such a campaign doesn’t need to be true or have any proof for its claims about the system, it will definitely hurt the voters’ trust in the system anyway – regardless of what the experts say.

David, when I understand it correct, I can verify that my vote is counted. This is something I applaud.

The question remains however: how exactly do I know that my vote is counted correctly?

Furthermore, in the event that the systems go down, or that the fair process is somehow compromised, how can a re-count be assured? And in case of a re-count, how can I verify that my vote is counted + being counted correctly?

You, as a voter, verify that your vote has made it correctly into the database with all the encrypted vote. You do this by comparing your encrypted receipt with the electronic version of it shown online (or on your newspaper’s website or your political party’s website) and then you can feel assured that your vote has been counted correctly. The reason for this is that if you make sure that your vote goes correct into the decryption and counting process, the public, in the form of newspapers, observers, political parties and a large number of experts, verifies that your vote is decrypted and counted correctly. You checking your vote is called voter verifiability and the public checking the rest is public verifiability. Those two kinds of verifiability put together makes a system that is end-to-end verifiable.

Verifiable electronic voting systems must be set up with robustness in mind. That means that every function in the system is handled by several servers or computers working in a threshold fashion, such that if a maximum of x out of y servers are compromised or go down, the system still works correctly.

If I understand correctly, you still have a single point of failure: the one who prints the forms knows what was the order of the answers in each form, and so can know from each publicly available scan what exactly was the voting. If he also knows how to match a specific form to a specific voter (for example, if he asks the voter for his receipt, or if both the scan order and people arrival order are known), then there’s no secrecy at all.

Do you have a solution for this?

There are a number of different solutions in the verifiable electronic voting literature, see my other comment about on demand printing.

What are your thoughts on dealing with the problem of printing the ballots without revealing the ordering of the questions on each ballot?

If you provide a printer with ballot images to print, then they can read the ordering of the questions off of the images and store them in a database that can then be used to decode the ballot receipts, and therefore, allow votes to be coerced.

This is absolutely right, we call this the chain of custody problem. If the ballot forms are centrally printed they have to be distributed without anyone being able to see them because if they can be seen then someone will know the contents of the vote after the election by looking at the encrypted vote online. So printing could be done centrally and the ballot forms kept secret in the printing facility using procedures that ensure that no-one gets to them and then they are put in envelopes from which they are only taken by the voter in the voting booth.

A different solution is called on demand printing and this would ideally be done in the polling station or even in the voting booth. So when a voter needs a ballot form it is printed there and then, making it hard for anyone to get a chance to look at it. This, however, comes with its own problems in the form of key distribution complexities: each printing facility in the polling stations would need its own private key and these would have to be distributed and kept secret using some procedures. So there is a trade-off here.

It seems to me that you also need to trust the authenticity of the software that generates/prints the ballots. There is no way a voter can know that the two parts of a ballot correspond, i.e. that the order of the candidates in the encrypted receipt corresponds to the order of the candidates as shown in the candidate list. While the voter can verify that her vote was counted she can’t know which candidate her vote was attributed to.

I suppose you could randomly test a certain small percentage of the ballots to ensure there is no structural fraud like this. But then again such a test would require trust in the officials performing it.

Spot on, Gary! Ballot forms are audited before, during and after the election (all remaining ballot forms could for example be audited as soon as the polls close) by election observers or even members of the public who would like to satisfy themselves of the correct printing of ballot forms before they vote.

Silly question. This is quite an impressive process, well thought out brilliantly explained. Though from this blog one can see the complexity level, and all the parts, and perhaps it could be very useful in providing alternative voting option for the minority in the western countries that do not have access to computers. But why go through all the hassle when theoretically I could just log on to the government website from my iPad in my PJs from the comfort of my home or from the beach wherever, and my vote would still be secret, very verifiable, no need for the immense effort of all the polling stations and paper and printouts and shredders! We all have bank accounts we use on line every day and pretty successfully so without any problems. In US we pay taxes on line! I now live in Colombia and my maids even have laptops here, access should not be a problem in the west. Why not just go on line? Or is this envisioned as an interim step before going on line? First get people used to validate their votes on line and next eliminate the inefficiency of the paper/printer/shredder operation and move to on line voting?

The reason we trust online banking is not that it is foolproof but that the bank sends us a statement at the end of the month and if money is missing from our account due to fraud then the bank gives us the money back. In fact, banks lose large amounts of money to fraud each and every day but this is simply a cost to them, comparable to that of having people visit bank branches to perform their transactions. This is not applicable in the election setting, we need a perfect tally of the votes as a foundation of our democracies.

Furthermore, if we vote remotely (over the Internet or by post), it is very hard to know that voters are not being coerced. Let’s say you get a password to log into the voting application, well I can just go from door to door and buy those passwords off people and then cast votes in their names. Party campaigners can go door to door and ask if you have filled out your postal vote and if not, help you do so and even take it to the nearest post box for you (as has already happened in the UK in the past). Or perhaps a dominant figure in the household votes for all the members of the household. Or religious or other leaders ask members to all vote together in the same place and the same time. These are the kinds of problems there are with remote voting in general, and they are so serious that I believe that only a controlled setting such as the poll station can ensure that we have free and fair elections.

David,

What is to prevent the original ballots from being forged so that the ordering of candidates is off? If the part of the ballot that tells the voter which square represents her choice is shredded, there is no way for anyone to verify that she wasn’t fooled into voting for someone she didn’t want. Elections could be manipulated in this way by predicting which candidates would be popular in which precincts.

As you know, Andrew Neff proposed a protocol for electronic vote casting which entangles the voter and the vote-counting computer in such a way as to provide assurance that the vote is counted as cast. Your system seems to lack this critical feature, although I’ll admit fraudulent ballots would have to be prepared in order to realize the attack I’m proposing here.

By the way, where can I read technical details of your proposal? Links here do not lead to any.

Ballot form auditing is a crucial part of the system: ballot forms are audited by election observers before, during and after the election. Any member of the public can also choose to audit one or more ballot forms before he or she casts her vote. After the election it is possible to audit all remaining ballot forms. The ballot form auditing is a process whereby the encrypted secret values are decrypted and published by the trusted parties and anyone can thereafter verify that the ballot form has been printed properly.

The name of the system is Prêt à Voter and it is developed by the electronic voting group at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK. All our research has been published in workshops and conferences such as WOTE, EVT, FEE and FEV, but what is lacking (as I have been telling the group for years) is good, publicly available information. A very good paper on Prêt à Voter has recently appeared in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security – Special issue on electronic voting with the title Prêt à voter: a voter-verifiable voting system. That should have the technical detail that you would want.

Hi David,

I have just finished reading through all the comments and your answers to questions posted here. Thank you for clarifying a number of points.

I still don’t get exactly how the auditing of ballot forms works. The youtube video titled “Voting With the Pret A Voter Prototype v1 ” shows a voter feeding the right hand side of the ballot form into the machine which produces the left hand side. Could you please clarify how this works? Is the machine connected to the trusted parties who decrypt the RHS on demand? Is that particular ballot form then made invalid?

Thank you very much

Feeding a blank ballot form into the scanner in version 1 of Prêt à Voter causes the system to audit the ballot form. The trusted parties are all involved in decrypting the underlying secret value where after the candidate list is recreated and printed. All the secret values (there are actually several in version 1, each under a separate layer of encryption) are published online (on what we call the “web bulletin board”) for anyone to audit. The printed version of the candidate list is produced to show the voter that the ballot form is correctly formed and she, or any interested person or organisation, can subsequently audit the values published on the web bulletin board.

Good TED talk, David! I like this idea so much! And I really appreciate how meticulously you address all questitons here.

After the voter audits a ballot form he obtains a fresh ballot. Is this because the ballot he audited becomes void?

May I suggest you update the article text above and incorporate your answers to some of the issues raised by all the comments here? Working through all the comments to find answers is a bit of a hassle 🙂

The ballot form has to become void when it is audited because it reveals secret information that can be used to prove what the vote is, if it is also used to cast a vote.

Thanks for your suggestions!

This sounds like a really great system. However there’s been a debate amongst my family about how the encrypted votes are actually read. I’m not well versed in cryptography but would it be possible to give a layman’s explanation about how you distribute the keys to decrypt the master table of encrypted votes, making sure that no one party can read the whole list and match everyone to how they voted?

[I edited the comment to remove quite a lot of text after this mark – sorry, but this makes the question clearer! /David]

The decryption of the encrypted votes is done by many different, distributed trusted parties. So (in simple terms) when all the encrypted votes have been collected, the first trusted party downloads them to its server, mixes them and perform its part of the decryption. The result of this mixing and decryption is then published online whereafter the second trusted party does the same thing. Then the third, fourth, fifth and so forth. There is no central point where the decryption is done or the key shares come together to form a master key, because the decryption is distributed like this. When the last trusted party has done its decryption the votes are in plain text and can be counted. The repeated mixing and decryption breaks the link between an encrypted vote (and thus its voter) and the plaintext vote. The mix is verifiable because the trusted parties publish proof that they have performed it properly, without revealing their mix.

What if any one of these parties boycotts the decryption process? If one of the parties, in protest over some aspect of the election, refuses to play their part in the decryption – does that scrap that entire election?

Does this splitting the master key between trusted parties rely on the virtues of the parties (choosing neutral organisations such as UN or some NGOs), or that the antagonistic relationship between them will make a conspiracy unlikely (opposing political powers)?

Well spotted! In the interest of being clear, I feel I have to try and not go into detail in many of my answers. One such detail is that the threshold cryptography used is such that if k out of n trusted parties (who each hold one key share) helps with the decryption then it can be done. Therefore n-k trusted parties can malfunction or stage a denial of service attack without this effecting the outcome of the election. One important purpose of setting the system up in the way that we propose is so that there is no single point of failure and that the power over the system is not placed in the hands of any one organisation.

When choosing n trusted parties it is important to choose them so that the probability that at least k of them are honest. Therefore, as you point out, organisations with diametrically different views and interests would be chosen, also large, international NGOs etc would be chosen because they would have a strong interest in maintaining their integrity.

Pingback: TEDtalk: E-voting

How do I, the voter, verify that not more votes were cast than people who actually came to vote at the polling station? Basically, how do you ensure that some corrupt official doesn’t manufacture a bunch of extra votes for the party he favors to win? This was an issue with some machines in the US, where it was known that only, say, 300 people went to a particular voting station on election day, yet the machine somehow recorded 1000 votes.

A controversial idea that is possible with encrypted votes such as the ones I show in my talk is that we can publish the encrypted votes next to the names of the voters who have cast them. In the process of decrypting the encrypted votes, the trusted parties irrevocably break the link between an encrypted vote and a plaintext vote so that the fact that your encrypted vote appears next to your name does not link you to a plaintext vote.

Because the encrypted votes appear next to the names of the voters who cast them, we can verify that the votes have been cast by eligible voters. And if you have not voted and a name appears next to your name, you know something fishy has happened.

I would love to see your system implemented in a small scale test election somewhere, with real people, over some real issue. And perhaps declare “open season” on it among hackers, etc, to see if it withstands any outside (or inside) attempts at tampering at any point in the process.

Do you know of any entities that are involved in doing real-life tests of this kind? I’m particularly interested in anyone in the US, though it would be good to know about others elsewhere as well.

David,

a presentation suggestion. The ballot in your demo (figures above)

https://verifiablevoting.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/img_2390.jpg?w=518&h=778

and following

presents some choices that refer to the electoral system, like

“would you be happy trusting your vote to an electronic system in a general election?”

May I suggest that that the demo ballot has choices not related to the subject matter of your talk? Such as “Would you prefer apples or pears?” or similar?

(It is something I find useful when teaching logic – avoiding ambiguity between language and metalanguage.)

Well it IS a minor point.

Roberto

This is very interesting. I live in a country where NO ELECTION IS CLEAN. I would really like to see your system being fully tested.

Very cool concept. What happens if the marks/numbers on the ballot are not legible? Does the scanner guess to figure it out, and then when you verify your receipt, you notice that the numbers don’t match up? Or does the scanner reject the ballot, and an official makes you re-vote?

Having people fill out numbers in digital digit form is confusing. I actually had to think how to print a 2 and 5 in that style. I imagine it would be difficult for seniors.

what about ballots with a lot of initiatives…do you make the paper longer? Is it double sided or two pages?

I would like to be able to verify my vote before the election is called.

What text fields are posted in the plain text document? encrypted number, district, etc?

There are many versions of Prêt à Voter now, with voters writing real numbers instead of the seven-segment thing and so forth. The scanner does check that it is a valid vote that it recognizes and if not, then you are allowed to exchange it for a new ballot form (if you spoilt your vote by over or under voting for example) and try again.

The recent turmoil, national and regional instability and many deaths resulting from disputed elections around the world, mostly Africa and Europe, highlight the need for something better. This solution should be championed by the UN as a (the?) primary peace tool. I have suggested Australia use this system and it is before the relevant commite.

As for taking photos of ballots, electronic free booths with magnetic fields could be used with restricted booths for those with medical exemptions could reduce but not eliminate the problem.

Or the booth could be designed where the voter could be observed from one side and the process of voting is concealed. Surely there can be solutions to this problem.

Best of luck with the system. I would be interested to hear how it goes.

With this system we understand how you can make sure your vote has been counted for. This reduces the possibility that fraud happens by removing votes for a candidate.

However, how about the other way around? How do you ensure ghost votes were not added to another candidate?

This is called “ballot box stuffing” and is a serious problem all around the world already. In fact, it is not specifically part of the work we have done so far. There are different ways of getting to grips with this problem and many countries around the world publish lists of all the eligible voters and all the voters who cast a vote in the past election so that people can scrutinise these.

I have a question about election rigging. I believe the system does not solve an essential problem of voting with paper. Assume I want to buy or coerce a vote and that I have some skills. I obtain an unmarked voting form by some means. I now threaten a voter or offer to buy a vote from a voter and obtain cooperation from the voter. I mark the form in the way that I want it marked and give it to the voter (intact) and record it. The voter goes into the voting station, ‘votes’ with my pre-marked page and returns with a newly issued blank form. In exchange for money or a promise the newly obtained form is given to me. I can now continue indefinitely.

In a conventional secret paper ballot the voter can spoil the vote. In the proposed system, the vote can even be verified by the vote-rigger. As long as it is possible to (secretly) remove the blank, officially issued ballot, the election can be manipulated.

Does the proposed system have a defense against this (old) form of vote rigging?

Regards

This is called “chain voting” and it is a very serious attack in any place where the ballot form is a restricted resource. And you are quite right that chain voting in this setting, where the coercer can check after the close of the election that the correct vote has been submitted, is a serious problem – but there are solutions proposed in the research community over the past few years.

Dr. Bismark,

I would like to implement an internet version of Prêt à voter and deploy it in Hong Kong for the

“2011 Election Committee Subsector Elections” of Information Technology subsector.

What kind of license that I need to obtain ?

Thanks,

Edward Yau

There is no license that you need to get to use the system as it has been published in scientific journals and papers. But you would then have to make an implementation of the verifiable voting system by yourself – please do get in touch if you want to discuss that further.

I have a question–I am a student helping a team that will be designing South Sudan’s future electoral system and I am very interested in your voting system. However, for cost purposes, I would need to tweak it a bit. How do I get in contact to discuss this further?

It’s great to be in contact with you now Danny. For anyone else who feel they might be able to use this kind of technology I can only say: get in touch! We are coming from the academic world so we are all about sharing the great ideas.

Is a ballot void if it’s audited?

That’s right, you can only either audit a ballot form or use it to cast the vote. The audit reveals information that you otherwise could use to prove to an attacker how you voted.

Most of the conversation assumes everything goes well & works. What happens when validations of all kinds fail. In the case of pre-printed ballots what happens if whole ballot boxes full suddenly show up from amongst those not used? What happens if whole boxes end up missing? What process goes on if a person finds his ballot has not been tallied. What happens to all the voting machines which we have today with data cartridges. You have a 50% chance to predict the randomization of two candidates – could two people who voted differently figure out which blob in the barcode is which? Once you have voting machines the system breaks down, doesn’t it?

Hi Mark!

The point of an end-to-end verifiable electronic voting system is very much that if anything goes wrong (votes go missing or are changed before they are counted, perhaps by a hacker) we will always find out. It is impossible in such a system to commit fraud without going unnoticed. On the question of “what do we do if we detect fraud” that is very much up to the country or precinct using the system – there should be guidelines in place on what to do. With regard to your question about the barcode the answer is no, the information in there is encrypted which means the different blobs do not have specific different meanings.

On your last point I would like to disagree – with end-to-end verifiable electronic voting, it is possible to finally have elections free of fraud – for the first time in the history of democracy.